|

|

Saturday, December 6th, 2008

So I'm thinking The Stone Raft may benefit, as The Black Book did, from a Google Maps approach to reading. I find myself struggling to remember which character lives where, and wondering about the course of their journey and the landmarks they see along the way. I'm thinking it would make sense to create a Google Maps view of Spain and Portugal with markers for locations referenced in the novel. A sampling of locations and landmarks I did not recognize from the fifth chapter would include among other things, Orce (a village in Granada and apparently the spot where the oldest human remains in Europe were found), Aracena (the town where Joachim and José spend the night), the Giralda (a public work of art of some kind in Seville*)... Also I need to find out who the Spanish poet Antonio Machado is, whom I believe I have seen referenced in Saramago before.

*Update: the Giralda is actually a piece of architecture, a bell tower -- depending on how loose your definition of "public work of art" is, it might fit; I had been thinking it was a statue.

posted evening of December 6th, 2008: Respond

➳ More posts about José Saramago

|  |

Friday, December 5th, 2008

This passage, at the beginning of the fifth chapter, is really striking: They have spoken about stones and starlings, now they are speaking about decisions taken. They are in the yard behind the house, José Anaiço is seated on the doorstep, Joachim Sassa in a chair since he is a visitor, and because José Anaiço is sitting with his back to the kitchen where the light is coming from, we still do not know what he looks like, this man appears to be hiding himself, but this is not the case, how often have we shown ourselves as we really are, and yet we need not have bothered, there was no one there to notice.

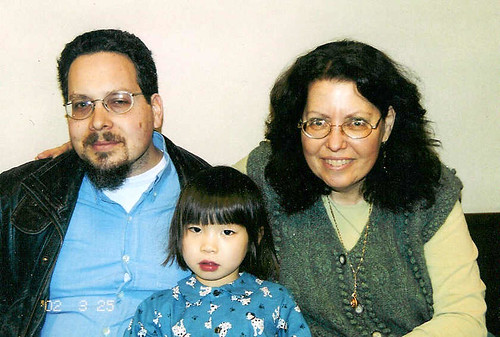

I can picture exactly how this would look in a movie. Sort of deep reds and shadow, with a light yellow incandescence coming from the kitchen door and window (I sort of think the door is ajar), when the camera (which starts with the two of them in profile, with shadows across them and the starry night behind) pans past Sassa at one point the window will be a frame of light around his head. (For some reason I am thinking of this as set at the back yard of the house of one of the Great Whatsiteers, who posted pictures of her back yard a few months ago -- if I can remember where that post is, I'll add the image to this post.*) This passage shows almost perfectly the ideal form of how Saramago structures his thoughts. The first sentence (the first sentence of the chapter) draws in the whole story so far, has an elegant, quick rhythm. Then period -- a moment to collect your thoughts. And charge into the second sentence, the long glissando with ups and downs, repetitions, speeding up and slowing down, and delivering you to another quick chord.

*(Aha! Found it.)

posted evening of December 5th, 2008: Respond

➳ More posts about Readings

|  |

Thursday, December 4th, 2008

People cannot hide their secrets even though they may say they wish to keep them, a sudden shriek betrays them, the sudden softening of a vowel exposes them, any observer with experience of the human voice and human nature would have perceived at once that the girl at the inn is in love.

It seems to me like Saramago walks a very fine line in his fiction. It is the stories of his characters that carry the books, that make you interested in the outlandish plots he is weaving. And I don't mean to say that the plots are dull -- they aren't, they are wild to imagine and the complications he touches on bear a lot of thinking about -- but it is the characters that engage me as a reader, that make the books real. That was the real failing of Death with Interruptions, the reason it seemed so mechanical and flat was the lack of any fully realized characters in the first half of the book. I am glad to see The Stone Raft does not suffer from any such failing. The primary characters -- who we have known by name since the first chapter and are really starting to come to the fore in the fourth chapter -- are fully human almost from the first mention; and even many minor characters mentioned only in passing are rendered well enough to give a sense of their humanity.

posted evening of December 4th, 2008: Respond

|  |

Sunday, November 30th, 2008

The first chapter of The Stone Raft is pretty dreamy. Saramago has got me wondering though, with his silent dogs of Cerbère, whose barking will herald the end of the world -- this seems like a weird detail to invent, but I'm not finding any reference to it with Google. I want to know if this is a real folk tale or a creation of Saramago's. And a couple of things to do with translation: what is referenced by "And to all appearances definitive," at the beginning of the last sentence of the long paragraph on pp 2-3? There is no obvious subject for the modifier. And on page 1, "a dog with three heads and the above-mentioned named of Cerberus," ("named" clearly a typo for "name") makes me do a double-take -- the name Cerberus has not been mentioned, although the French form of that name is Cerbère, the same as (though etymologically unrelated to) the village where the dogs are barking. Is Saramago counting on the reader to know this? Or is the Portuguese form of Cerberus the same as the French?... This chapter consists mainly of introducing some characters by name and discussing what they were doing at a particular moment in time, the moment (as I know from reading the blurb on the back cover*) when Iberia breaks away from the continent of Europe. It is cute and whimsical -- but there are some passages that pull the reader below the surface to look at the underpinnings of the structure that this novel will build. José Anaiço is walking through a field at the fateful moment, when a flock of starlings rises into the sky and wheels around.

...birds don't have reasons, just instincts, often vague and involuntary as if they were not part of us, we spoke about instincts, but also about reasons and motives. So let us not ask José Anaiço who he is and what he does for a living, where he comes from and where he is going, whatever we find out about him, we shall only find out from him, and this description, this sketchy information will have to serve for Joana Carda and her elm branch, for Joaquim Sassa and the stone he threw into the sea, for Pedro Orce and the chair he got up from, life does not begin when people are born, if it were so, each day would be a day gained, life begins much later, and how often too late, not to mention those lives that have no sooner begun than they are over, which has led one poet to exclaim, Ah, who will write the history of what might have been.

(And what poet was that? Google gives no results except from this book. Perhaps an invention of Saramago's, perhaps something that has not yet been translated to English in this precise wording.)A beautiful passage a few pages before this one is the first point where Saramago addresses the audience, asks us to consider what we are doing when we sit down and start reading the story he has composed:

Writing is extremely difficult, it is an enormous responsibility, you need only think of the exhausting work involved in setting out events in chronological order, first this one, then that, or, if more conducive to the desired effect, today's event before yesterday's episode, and other no less risky acrobatics, presenting the past as if it were something new, or the present as a continuous process with neither beginning nor end, but, however hard writers might try, there is one feat they cannot achieve, and that is to put into writing, in the same tense, two events that have occurred simultaneously,... The people who come off best are the opera singers, each with his or her own part to sing, three, four, five, six in all among the tenors, basses, sopranos and baritones, all singing different words, the cynic mocking, the ingénue pleading, the gallant lover slow in coming to her aid, what interests the operagoer is the music, but the reader is not like this, he wants everything explained, syllable by syllable, one after the other, as they are shown here.

And I think oh gosh, this beautiful prose! It washes pleasantly over me but gets even better when I pause and examine it more closely. The rhythm of phrases and commas and repetitions and the power of the period.

* A mildly funny thing about the blurb: it was written in ’96 and says Saramago is "Winner of the prestigious Independent Foreign Fiction Prize" -- I'm used to thinking of Saramago as the winner of the prestigious Nobel prize for literature but of course he was not always that.

posted morning of November 30th, 2008: 2 responses

| |

|

Drop me a line! or, sign my Guestbook.

•

Check out Ellen's writing at Patch.com.

| |

Bill Ayers

Bill Ayers  Cyrus

Cyrus